What we learn from Ordnance Survey maps

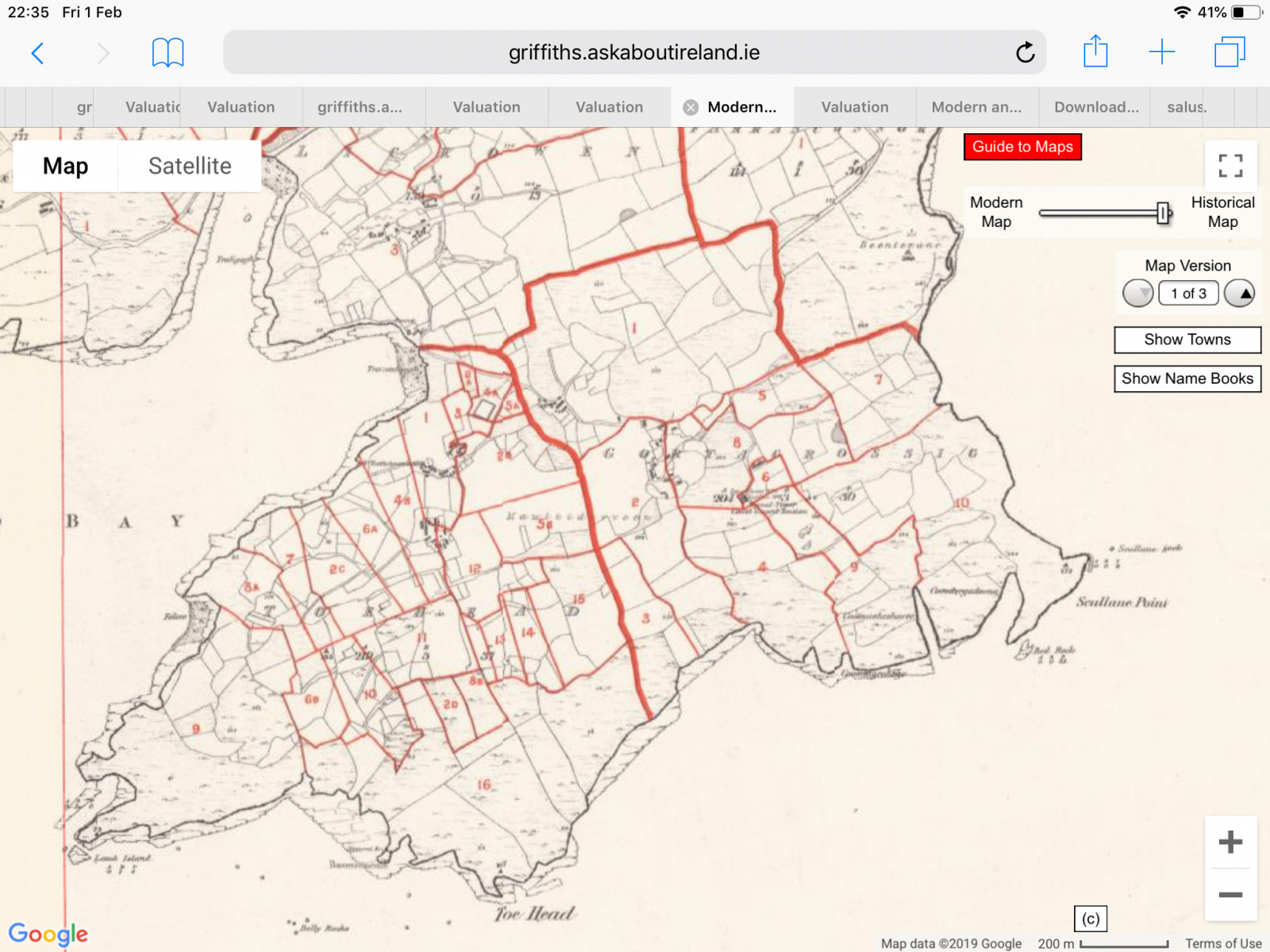

Ireland, in the 19th century, was probably the most extensively mapped country in the world. Between 1829 and 1846, the Ordnance Survey mapped the entire country in extraordinary detail using a 6 inch to the mile scale. Every house, field and even the most minor landmark was recorded with incredible accuracy. This has left us with a remarkable historical record that allows us to compare the Ireland of today with that of almost 200 years ago. The maps that accompany Griffith’s Valuation (carried out between 1847 and 1864) readily show us how much Ireland had changed as a result of the devastating famine period. Within the space of twenty years, agrarian practices had been transformed and this is very clearly the case in the south Castlehaven area where the clachans were broken up and farmsteads on individual family-farmed plots of land were established. Remarkably, Scobaun and, more especially, Toehead still retain something of their original clachan formation to this very day.

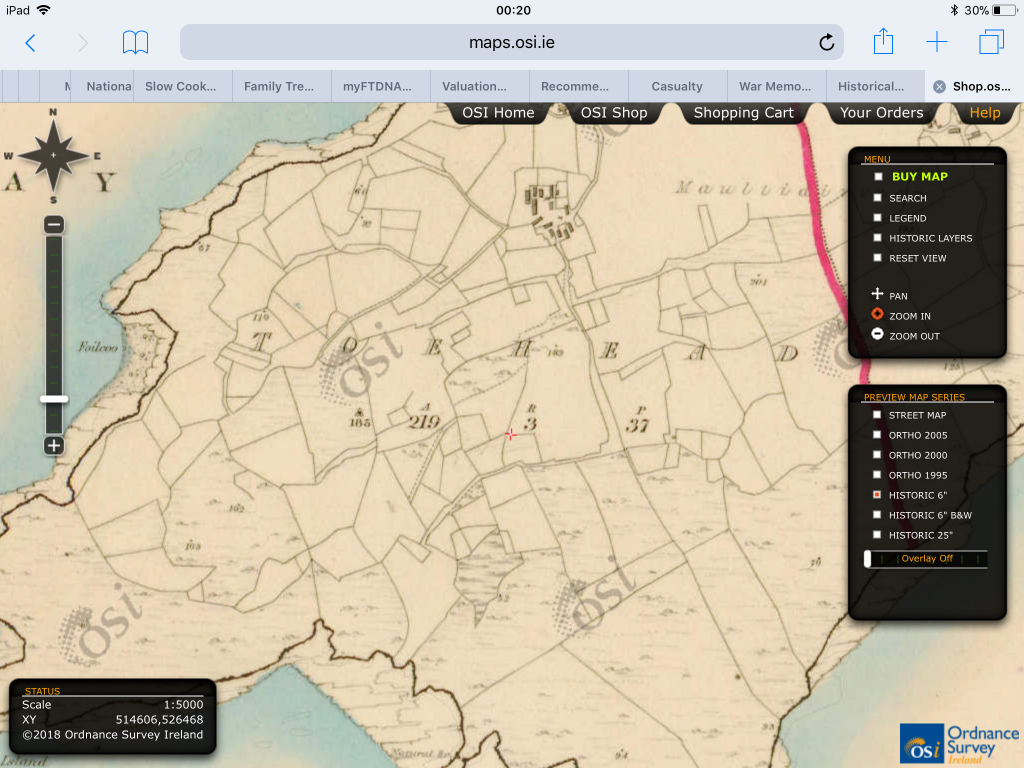

The pre-famine map above demonstrates clearly the presence of the old rundale agricultural system in operation on Toehead at that time. The houses were grouped together in a clachan and land was divided up among the tenants with each family having a generally even distribution of good quality and poorer quality land. These clachans were not villages as they provided no services such as shops, churches or schools. They were simply clusters of farm cottages and, as such, are the townlands that are the basic unit of territory throughout Ireland. The families were sometimes related but not necessarily so but these neighbours formed tight-knit groups where neighbours worked together to sow and to harvest and to share the primitive tools they may have owned. On Toehead the families were Sextons, Burkes, Sweeneys, Cronins, Sheehans, Hollands, Hourihans, Keohanes, Hurleys, Cains (Keanes), Dwyers and Wests while in Scobaun there were Sextons, Hourihans, Sullivans, Henrys and Driscolls. Sometimes, there were two or more families of the same name who were often closely related.

The land closest to the clachan would generally have been of good quality and used for the growing of crops of which the potato was by far the most common. There may also have been smaller amounts of grain grown. Further away from the clachan, the rougher land would have been used for the grazing of cattle. This land was usually commonage with each family entitled to graze a specific number of cattle. The the south of the headland was an area of very rough, poorly-drained land known as the Móin Rua (or ‘red bog’). There was probably a certain amount of turf available in this area which would have been dug out, dried and used for fuel. It was probably quite a shallow bog so the turf would have been of poor enough quality. Farming was very much at a subsistence level with all families surviving almost exclusively on a diet of potatoes and buttermilk.

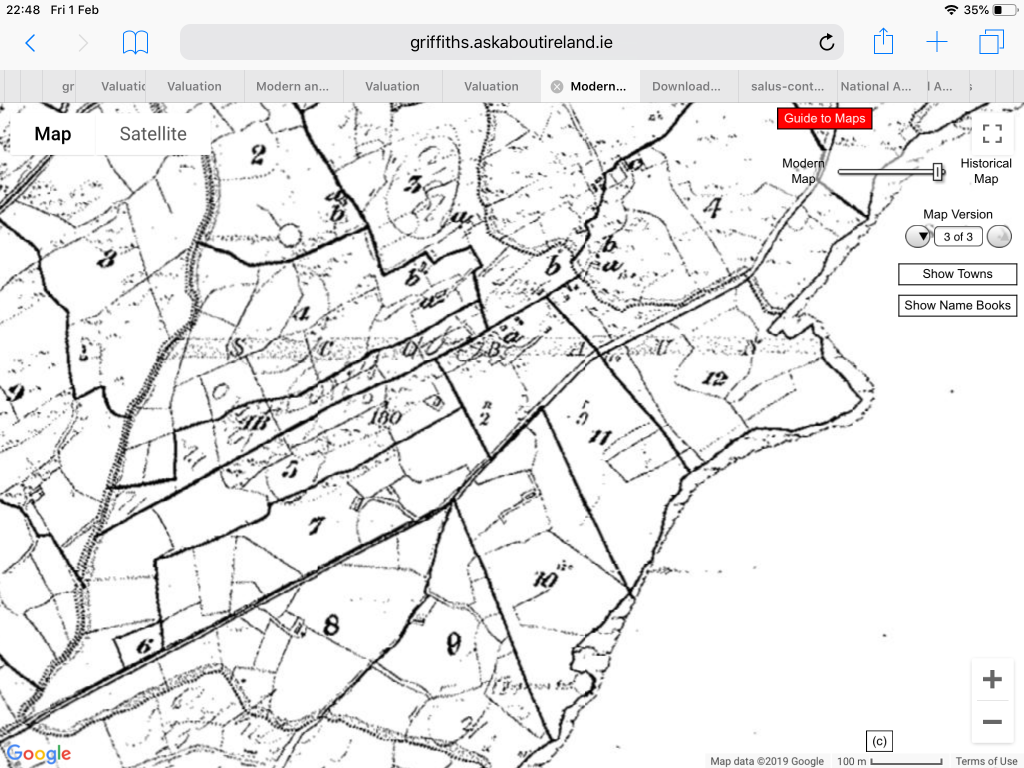

By the time of Griffith’s valuation (which was completed soon after the famine), we see that the pattern of farming had been radically altered in Toehead. Each individual family has its own holding with the Sexton holding being Lot 11 (divided between brothers Cornelius and Patrick). In time, families would abandon their houses in the clachan and build new houses on their own holdings. So it was with the Sextons with Cornelius and Patrick building small stone-built houses, within metres of one another on Lot 11. Neither house has yet been built however at the time when this map was drawn up. For the moment, both Sexton families are still living in the clachan and travelling out each day to tend their fields.

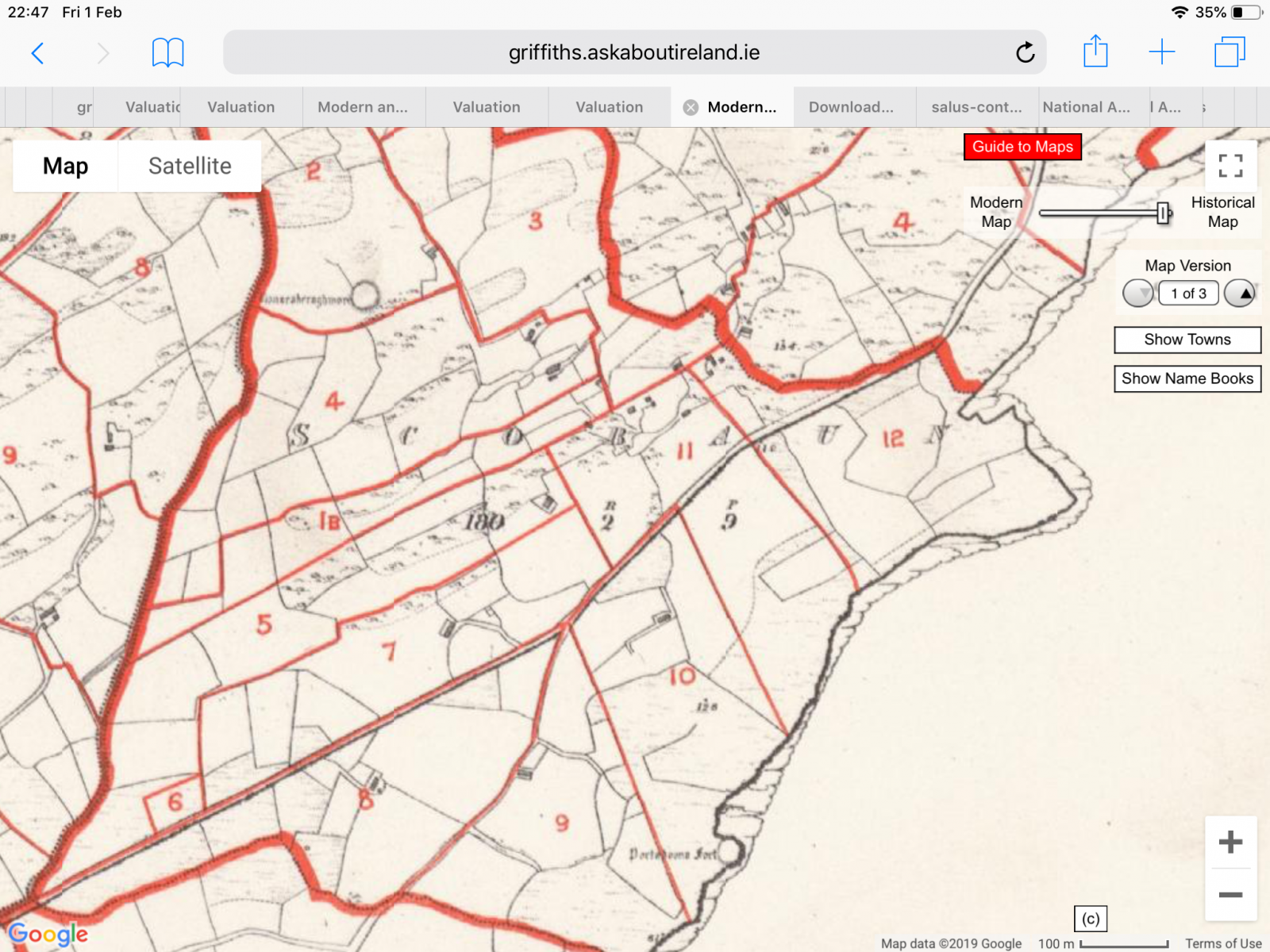

What is interesting from examining the Griffith’s Valuation map of Scobaun is how remarkably stable the landholding remained in the townland between 1850 and 1950. Many of the farms were still in the same hands a hundred years later and where land did changed hands the holding remained intact. Much of this may be due to the fact that the landlord for the townland throughout most of the 19th century was the French family of Cuskinny near Cobh. The Frenches seem to have been benevolent landlords as there is no folk memory of evictions during or after the famine period. In fact, while John Sexton of Scobaun died in the Skibbereen workhouse in 1847 during the height of the famine and was described in loan documents as being a pauper, his holding remained in his family after his death.

We also see that there are two houses close together on Lot 4 – only one of which remains today. The northern one is the existing Sexton home (now owned by Clodagh O’Meara). The southern one appears to have been demolished when the second Sexton family built a new house on their own landholding (lot 5) many decades after this map was made. We also notice the presence of a ring fort on lot 2. Today there is no trace of this fort. Perhaps the single biggest landscape change between the map and the reality on the ground today is that almost every field boundary has been removed from lot 4 as the new owners of the land (Buckleys have moved into intensive grazing of livestock. Consequently the field names of Lot 4 which tell so much of the agricultural practices of times gone by no longer define any given area. The field names were: Páirc a’choirche, the linga, the lacka, the north, middle and south meddas (meadows), lower and upper páirc a’ sparraigh, parkynaile (Páirc Uí Néil?), Garraí Eoin , the páircín, the clós.