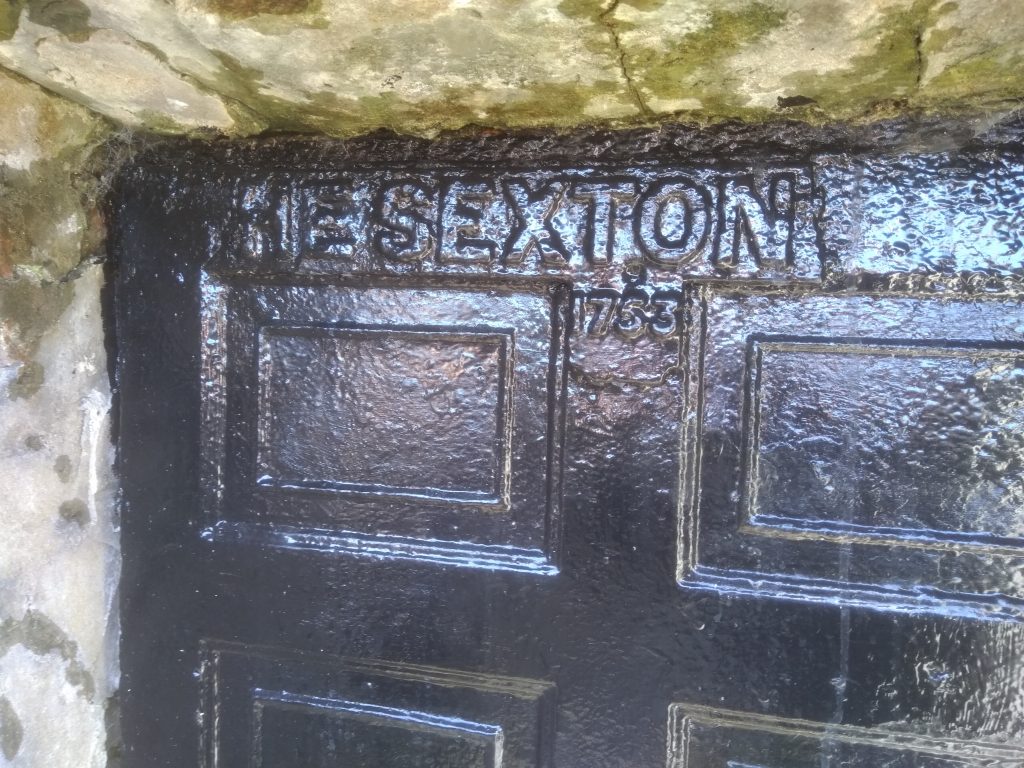

Edmund Sexton and the origins of the Limerick City Sexton family

In the middle of the 1400s, a Denis Sexton (Donncha/Donagh Ó Seastnáin) appears to have made his way from the lower Shannon area (probably the Tipperary side of the river) into the medieval city of Limerick. He had at least three sons – one whose name is unknown, a second named Denis and a third named Morris. Morris’s third son, Edmund, was to become a prosperous and somewhat controversial figure in the history of Limerick. Edmund’s mother was a Nagle and he had several brothers (Humphrey, Nicolas and Murtagh ‘the Hunt’ along with five sisters Amy, Alson, Anstance, Julian and Margaret. He was married to Kathren Arthur, a member of the prestigious Limerick family of that name.

Becoming established in the city

According to Clodagh Tait’s essay in Archivium Hibernicum Vol 56 (2002), the Sextons appear to have been merchants of some sort and were certainly property holders by mid 1530s. The family were known to be of Irish/Gaelic origin but this doesn’t seem to have been any barrier to their progress – particularly as these enterprising men seemed to have a flair for business and were apparently willing to do whatever was necessary to ensure their advancement. The fact that they had adopted English names (or English versions of Gaelic names) indicates a definite willingness to adapt to the new order. Edmund was involved in the importation of gunpowder from Flanders and served, at one point, as a servant to the Earl of Kildare. He, along with his brother, Humphrey, journeyed to London in 1533 as part of the entourage of the Countess of Kildare and acted as a messenger between the Royal Court and Kildare.

Prosperity and notoriety

When Humphrey returned permanently to Ireland and to the service of Silken Thomas, Edmund decided to stay and soon became a favourite of no less a figure than King Henry VIII. For the next couple of years, Edmund became Henry’s emissary and was described by Henry as ‘ a trusty and wellbeloved servant’. Edmund was part of Thomas Cromwell’s network of Irish ‘diplomats’ and was rewarded by he and his brothers being given burgess status in Limerick. Edmund had, in effect, become the Crown’s man in Limerick and took part in military operations in Tipperary and Waterford. In 1535, Edmund was elected Mayor – probably at the behest of Thomas Cromwell. Clearly this ‘election’ wasn’t greeted with any great enthusiasm by the people of the city who saw him as an upstart native who was getting much too big for his boots. The fact that he was of ‘Irishe bloode’ did little to endear him to his fellow citizeens. His influence at Court did, however, result in the granting of a Charter for the City along with acquisition of a canon of some sort together with shot and powder. During his time in London, Edmund who was clearly a well educated man, wrote a book (which hasn’t survived) on the ‘reformacon’ in Ireland. He also wrote books on the geography and economy of Munster and discussed how the country might yield greater revenues for the king.

Overcoming all obstacles

Through the late 1530s, Edmund continued in his role as unofficial emissary and acted as a go between between the Court and all the big players, both Gaelic and English, in the south of the country at the time. He grew increasingly unpopular with the inhabitants of Limerick, however, as he appears to have had a hand in the imprisonment of a number of prominent citizens who were accused of aiding Murrogh O’Brien and other rebels. In retaliation perhaps, Edmund was accused of mismanagement of revenue and for releasing a friar who had preached against the king. Within a short period, he had become a reviled figure who had sought to interfere in the lucrative trade that was well established between the city and the Ango-Norman lords and Gaelic chiefs who controlled the rural areas beyond the city. He also stood accused of having taken possession of tracts of land following the dissolution of the monasteries in Limerick – land that the Corporation felt was rightfully theirs. He was imprisoned in Dublin Castle but Edmund put up a stout defense, pointing especially to his service to the Crown and to the fact that he had had great influence in ‘bringing in’ the Earl of Desmond. The new Lord Deputy, St Leger, seems to have taken the view that Edmund’s crimes were no worse than those of his accusers and he was soon released. Even better, his claims to ownership of the dissolved monastery lands were confirmed. These lands were to form the basis of the landed estate that transformed the fortunes of the Sexton family.

Decline and fall

Before long, Edmund had fallen out with St Leger and Desmond and he again found himself called to Greenwich to account for himself. Against all the odds, he was pardoned but this didn’t save him from the ongoing emnity of the Earl of Desmond who eventually forcibly repossessed disputed lands at Corbally, a short distance outside the city. Instead, the Sextons allied themselves with the Butlers, Earls of Ormond, and took on board the ‘proto-Protestantism’ that the Butlers had adopted. Edmund also cultivate a friendship with Bellingham, the new Lord Deputy, who went so far as to propose to the citizens of LImerick to reappoint Edmund as Mayor (they politely refused!) Soon after, Edmund fades from the Limerick spotlight and he died in about 1554. There was some suggestion (made by his grandson) that he was murdered by his doctor.

Protestantism – religious conviction or flag of convenience?

While Edmund was, undoubtedly an opportunist, willing to consort with whoever was most likely to aid his advancement, there appears to be no doubting his commitment to his Protestant beliefs. Limerick, in the 16th century, never embraced Protestantism with any great enthusiasm and the Sextons were one of a very small number of Protestant families in a city that clung quite steadfastly to the old religion.

Ritualistic mutilation

It is unclear whether Edmund’s duplicitous nature or his religious beliefs were responsible for his unpopularity but sometime after his death, his body was removed from its tomb at St Mary’s Cathedral (allegedly by Alderman Christopher Creagh, Mr White, Edmund’s brother-in-law, and David White, the church organist) and hanged upside down in a concealed space between the roof and the rafters. The right hand was removed from the corpse and relaid in the tomb. Clearly, there was a ritualistic element to the manner of this mutilation and extraordinarily, the inverted corpse was not discovered until a number of years after Edmund’s burial when a thief was apprehended having sought refuge in the roof of the cathedral. Edmund’s grandson, himself an Edmund, suggested that his grandfather had been killed ‘for his religion’ but there is probably more to it than that as no other Protestants were mutilated in this way in the mid 16th century. Colm Lennon has suggested that many may have resented the way in which Edmund had enriched himself at the expense of the monasteries that had been dissolved and, perhaps more especially, at their expense. The Creaghs may also had opposed the Edmund’s burial in a part of the church that they felt was reserved for them.

Edmund was undoubtedly a most unusual man, full of contradictions. Given his Gaelic origins, he was an outsider but, above all else, he was a great survivor, able to adapt to a rapidly changing world. Again and again, he extricated himself from tricky situations and often profited from the experience. In a reversal of the famous phrase, one might say that he became ‘more English than the English themselves’, adopting their religion, their language and their customs.